Today we will be featuring another figure from our Perseverance and Persistence walking tour that we will be holding this Saturday at 2:00 PM at Elmwood Cemetery.

Lea Demarest Taylor was a remarkable woman in many ways. Her family were followers of Jane Addams ideas on Social-Welfare reform and Lea would make it her life’s work to continue in these reform efforts.

Lea Taylor was born in 1883 in Hartford, Connecticut. She was the daughter of Graham Taylor, a graduate of Rutgers and a member of the esteemed Taylor family.

Graham Taylor came from a long line of ministers and became one himself, attending the New Brunswick Theological Seminary after his stint at Rutgers. His work with the Dutch Reformed Church and with his ministry more broadly brought him into contact with poor immigrant communities, which would leave a lasting impact on him.

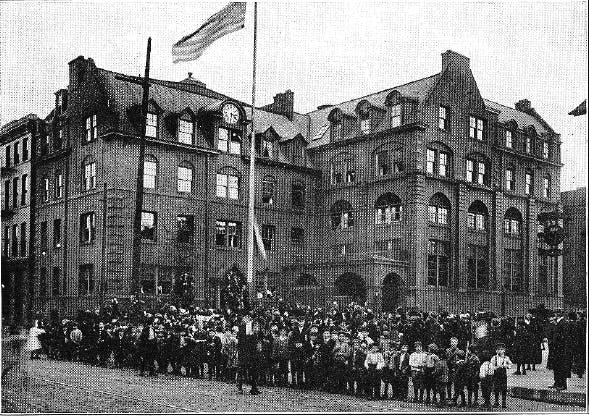

In 1892 Rev. Taylor accepted an invitation to begin teaching at the Chicago Theological Seminary. Early in his time in Chicago he became inspired by Jane Addam’s work establishing Hull House in the city. Having established the department of Christian Sociology at the Seminary, he was deeply interested in social issues and quickly established the Chicago Commons Settlement in 1894. Moving his family into the settlement, he lived amongst working class Scandinavian, Irish, German, and Italian immigrant families. Although the commons were secular, he brought in his seminary students as teachers and residents of the Commons.

Lea Taylor was but a child when she moved to Chicago with her family. Growing up in the environment that she did was a great influence on her outlook on life. Work was shared amongst the residents of the settlement and she embraced that lifestyle full heartedly. By the time she was 16 she had become a full resident of the commons, a title bringing with it a salary and many responsibilities.

Even though her social life and work responsibilities remained with the Commons, she attended school all the while, attending the Lewis Institute in 1900 at a high school level. For her higher education she would attend Vassar College, graduating in 1904. Unlike her father, she would not go on to graduate school, instead returning to the Commons and her father.

Lea would take on the responsibility of assistant and secretary to her father. Her other work included helping to edit the Commons’ editorial, which focused on local neighborhood issues, about which she was always passionate. She was also focused on community issues larger than just the settlement, however, as she became active in 1909 with the Chicago Recreation Commission. She would also become Chair of the Wider Use of Schools Committee.

In 1911, when Lea’s sister Katherine received an academic fellowship in Europe, the two travelled overseas together so that Lea could view European settlement houses and bring their ideas and concepts back to the United States; this work was extremely valuable as she was a member of the Chicago Federation of Settlements, which was established by Jane Addams, Mary McDowell, and her father. This organization would later lead the way to the National Federation of Settlements, which increased the reach of her work.

Her father had replaced her as secretary after she had left, allowing her to take on more administrative work. In 1917, five years after having returned from Europe, she became Assistant Head Resident of the settlement house, taking on additional responsibilities for budgeting, fundraising, and public speaking.

This coincided with America’s entry into World War I, and, as you may expect, the settlement house participated in the war effort as did so many other Americans. The Chicago Commons operated draft board Local No. 39. Residents helped to interview prospective draftees and explain procedures and policies to the neighborhood, which was largely made up of immigrants.

In 1921, Graham Taylor would retire from administrative duties at the Chicago Commons settlement, with Lea being chosen to replace him as Head Resident. This was a culmination of the work she had been doing for years, especially as her father had already been handing over more and more administrative responsibility to her while she was the Assistant Head Resident.

Lea Taylor would remain in her position as the Head Resident of the Chicago Commons during periods of great social, political, and economic strife. During the Great Depression, as unemployment levels rose, so did the number of those requiring public relief. She responded the best that she could as more poor people and immigrants moved into the squalor of city neighborhoods, made worse by a reduction in housing caused by multiple house fires in the neighborhood.

She would still try her hardest to accommodate these new individuals in need of her service. To respond to an influx of Spanish-speaking immigrants, for example, she adjusted the programs of the settlement house to meet their needs. Taylor would also use her voice as a social reformer and as the director of the Chicago Commons Settlement House to lobby for more aid.

The Chicago Commons led all other settlement houses in pushing for relief stipends and jobs programs. Lea Taylor would herself become the first woman to become a member of the Metropolitan Housing and Planning Council, where she pushed for more housing. She also encouraged improvements to existing sub-standard housing after serving as on coroners’ juries investigating deaths caused by the poor quality of their homes.

Lea Taylor was also very much opposed to segregation and encouraged racial integration of the neighborhood that the Commons Settlement House was in. The 1940s and 1950s saw an increase in African-American residents into a previously white neighborhood which led to racial strife, despite the efforts of community leaders such as Taylor.

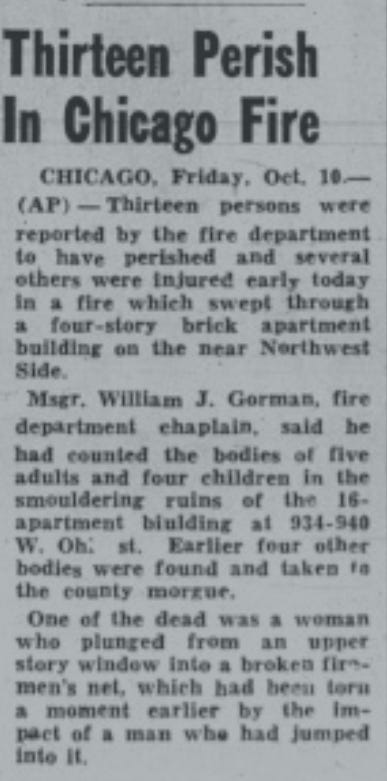

The worst came to pass on October 10, 1947, when a blaze would erupt in a 4 story, 16 apartment building at 934-940 West Ohio Street, a stone’s throw away from the Chicago Commons. A great portion of the occupants of the building were African-American. Between ten and thirteen perished, including a girl only the age of twelve. Most of the victims of the fire were known by those at the settlement house. Believing they were victims of racially motivated violence, she described the fire as “the inevitable that we feared,” and “the worst disaster in the field of inter-racial warfare that has happened in Chicago.”

Taylor had been a first hand witness to the crisis and devoted her energy to assisting the victims. Despite there being little room for the survivors the settlement house was open to them while she went to the morgue to give a report. The following morning she led a group to meet with Mayor of Chicago Martin Kennelly. They demanded a jury look at the incident, which he agreed to include in the coroner’s inquest. While it could not determine who may have committed the act, the jury did believe arson was the cause, and furthermore it criticized both the property owner for his negligence in making the building safe and suitable for living in, and the city of Chicago for safety regulations which were not stringent enough.

1947 would mark the beginning of the end for the Settlement House, as the Kennedy Expressway would start being built in the neighborhood. Residents would begin to move out and in 1948 the Chicago Commons Settlement House would merge with Emerson House to create the new Chicago Commons Association. Lea Taylor would retain her title as head resident, but William H. Brueckner, who was the head worker at Emerson House, would become the director of the organization. The Chicago Commons Association would move away from settlement living and instead establish community centers and buildings all across Chicago; they continue to operate to this day.

From 1950 to 1952, Lea Taylor would serve as president of the National Federation of Settlements. She would continue to focus on housing, integration, and anti-poverty programs. She would also return to Europe, still interested in their settlements.

Lea Taylor would retire in 1954, moving to Highland Park near Chicago. She remained on the boards of Chicago Commons, the National Federation of Settlements, and the Metropolitan Housing and Planning Council. For a time she would be a member of the Highland Park League of Women Voters and would help found the Highland Park Committee on Human Relations.

She would remain close to her family from this area, traveling to New Brunswick multiple times throughout her life. Her father had purchased a lot at Elmwood while he lived in Chicago and would be buried here, as would she. Lea Demarest Taylor passed away at the age of 92 on December 3, 1975 in Hightstown, NJ, leaving a legacy of social reform in her adopted home of Chicago.

Sources:

Allen, Joe. People Wasn’t Made to Burn: A True Story of Race, Murder, and Justice in Chicago.Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2011.

“Chicago Commons.” Social Welfare History Project, February 26, 2018. https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/settlement-houses/chicago-commons/.

“Chicago Honors Lea Taylor.” Social Service Review 29, no. 1 (1955): 75–75. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30019949.

Hajo, Cathy Moran, ed. “Taylor, Lea Demarest (1883-1975).” Jane Addams Digital Edition. Accessed March 1, 2024. https://digital.janeaddams.ramapo.edu/items/show/6422.

“Lea Demarest Taylor Papers, 1894-1969.” Special Collections and University Archives Finding Aids. Accessed February 29, 2024. https://uic.cuadra.com/star/findingaids/MSTAYL66.xml.

“Taylor, Lea Demarest.” VCU Libraries Social Welfare History Project, October 12, 2016. https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/people/taylor-lea-demarest/.

“Taylor, Graham.” VCU Libraries Social Welfare History Project, October 12, 2016. https://socialwelfare.library.vcu.edu/people/taylor-graham/.

“Thirteen Perish In Chicago Fire.” The Rocky Mountain News. October 10, 1947, Sunrise edition. https://www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org/?a=d&d=RMD19471010-01.2.12&e=-------en-20--1--img-txIN%7ctxCO%7ctxTA--------0------.

Wade, Louise Carroll. “Chicago Commons.” Encyclopedia of Chicago, 2005. http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/244.html.