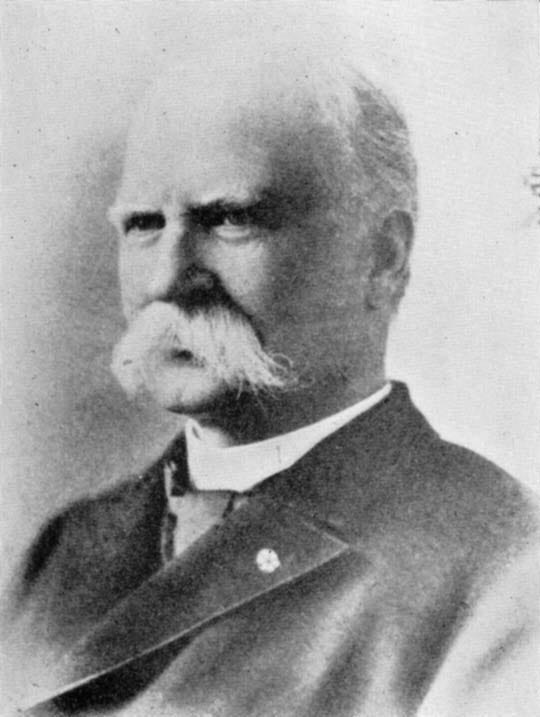

As I covered in last week’s blog post, Dr. David Murray was invited to teach mathematics at Rutgers in 1863 by President William Campbell. In response to the Industrial Revolution, Dr. Murray worked with Dr. George Cook to lobby the state of New Jersey into making Rutgers the land grant college of the state. Prevailing over Princeton in 1864, who was also lobbying for this position, Rutgers was charged with offering educational access to a wider range of students in order to cultivate a new workforce and the next generation of thought-leaders. Together Dr. Murray and Dr. Cook also worked to create a science program at Rutgers. At the same time, more and more students from Japan came to study at Rutgers, and Dr. Murray was among the most popular professors that these students had. It is in this context that we can understand the next chapter of Dr. David Murray’s life.

Japan’s government was undergoing a modernization to keep it competitive with its western peers. Consequently, Japan would reach out to western figures to enact changes to Japan’s government and society. One of these figures was Dr. Murray. It began when Iwakura Tomomi, one of Japan’s most influential statesmen and member of government, began a two year tour of Europe and the United States, with the purpose of renegotiating unfair treaties and to observe what western influences might be beneficial to Japan. He arrived in America in 1872. While his time in America was widely reported on, he was unsuccessful in influencing the American government to renegotiate any treaties.

Still, he did not leave America without any success. His two sons had studied at Rutgers, and Dr. Murray was a beloved professor by both of them. It is perhaps unsurprising then, that when the time came to look for figures that could help influence education in Japan, Dr. Murray was looked at. While this might seem like Dr. Murray had a leg up in the selection process, that wasn’t necessarily the case. Iwakura had turned over the matter to the Japanese legation in Washington, which reached out to educators all over the country. Still, Rutgers did hold significant sway as it was one of the earliest western institutions to receive Japanese students, so President of Rutgers William H. Campbell’s words did hold much influence. Knowing of Dr. Murray’s interest in Japan, he was naturally recommended for the role.

Dr. Murray would head to Washington to meet and interview with the Japanese legation. This would lead to more interviews, and ultimately Dr. Murray would be accepted to advise the Japanese government. Given his long career in education, in 1873 Dr. Murray would be appointed to be the Superintendent of Educational Affairs for the Imperial Ministry of Education, which was founded only two years earlier, in 1871. Because his work began at the beginning of Japan’s education administration, he would become, and remains, an influential figure in the development and structure of Japan’s education system. He would be granted a three year leave of absence by the Rutgers Board of Trustees; this was the length of the period that Dr. Murray’s appointment was set to last, although he would ultimately serve the Japanese government until 1879, a total of six years.

One can only imagine the sort of feelings that Dr. Murray must have been dealing with when deciding to take on this responsibility. He had devoted so much of his career to Rutgers and to New Brunswick more broadly. He was loved by the Rutgers community, as evidenced by the Board of Trustees decision to grant him a leave of absence. A historical club would hold a public dinner in his honor and Rutgers Class of 1873, which graduated only a few months before he left for Japan, would gift him an elegant traveling case. It was clear that his community here would miss him, and it’s not hard to imagine that he would miss his friends and students here, as well. Still, the chance to be the second highest ranked education official in Japan was not an opportunity that could easily be turned down, especially when he had for years spoken to his Japanese students about ways the education system could be improved.

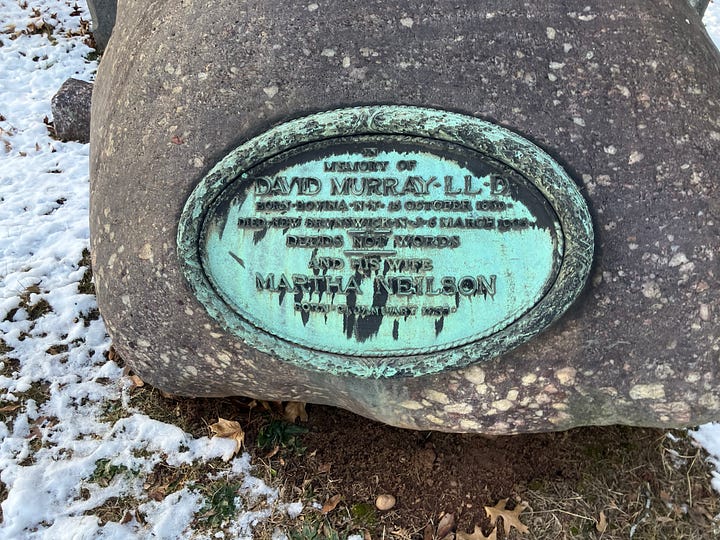

Dr. Murray’s wife, Martha Neilson came to Japan with him; her work as a hostess was essential and under-appreciated in maintaining Dr. Murray’s work. In his time as Superintendent, Dr. Murray was expected to host government officials very often, so his wife’s presence was very important in keeping up social appearances. Mrs. Murray actually had some Japanese students at Rutgers begin to teach her their language before she and her husband set off. While neither of the Murrays could be said to be fluent in the language, however, and her attempt to give a speech in the language caused some confusion; this incident apparently later became a favorite story of the Prime Minister.

Dr. Murray’s crowning achievement was the founding of the Gakusei, which was the first public school system launched in Japan. It provided educational access to all elementary school-aged children in Japan, and many consider it the beginning of modern education in Japan. In addition to his work in Japan, Murray did return to America in 1876 to attend the American Centennial World’s Fair in Philadelphia with the Japanese delegation, where he sought to acquire items for the newly established education museum in Tokyo. Finally, in 1879, he resigned his post, and after a tour of Europe, returned to America.

After he moved back to New Brunswick he became secretary of the Rutgers Board of Trustees until 1904. He passed away a year later, in 1905. There were once Japanese pine trees surrounding his headstone to memorialize his international travels and work, although they have since been removed from his gravesite. At the 150th anniversary of the college, representatives of Tokyo Imperial University spoke, in part, to honor the work of Professor Murray. Dr. Murray is remembered even today, as Rutgers has been taking steps to remember its connection to Japan in the 19th century. Certainly, Dr. David Murray’s story is one that deserves to be more widely known, and I’m grateful that we can play a small part in remembering his life and legacy.

Sources:

Cha, Rachelle Y. “David Murray.” Rutgers Meets Japan: Early Encounters, January 31, 2020. https://sites.rutgers.edu/rutgers-meets-japan/david-murray/.

Chamberlain, William Issac. In Memoriam, David Murray ph. D., LL. D., Superintendent of Educational Affairs in the Empire of Japan, and adviser to the Japanese imperial minister of education, 1873-1879. New York, NY: Priv. Print, 1915.

Duke, Benjamin. Dr. David Murray: Superintendent of education in the Empire of Japan, 1873-1879. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2019.

“Iwakura Tomomi.” Scholars Junction. Accessed January 14, 2025. https://scholarsjunction.msstate.edu/julia-grant-world-tour-photographs/44/.

Loy, Stephanie, and Priya Agarwal. “First Japanese Students at Rutgers.” Rutgers Meets Japan: Early Encounters. Accessed December 23, 2024. https://sites.rutgers.edu/rutgers-meets-japan/first-japanese-students-at-rutgers/.

Munez, Everett. “Sakoku.” Encyclopædia Britannica, April 18, 2023. https://www.britannica.com/topic/sakoku.

Reischauer, Edwin O., and Marius B. Jansen. The Japanese today: Change and continuity. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1995.

Sidar, Jean Wilson. George Hammell Cook: A Life in Agriculture and Geology. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1976.